Focus: Western region, investing in the west

Western counties thrive on tourism while abundant educational resources and improving infrastructure attract business.

By Katherine Snow Smith and Kathy Blake

Western North Carolina is known for its majestic mountains and wildlife, breweries and wineries, small shops and the biggest house in the country. The region has been popular with tourists for well over a century, and in recent years, it also beckons a steady stream of businesses.

Asheville-based Biltmore Farms, founded in 1897 by George Vanderbilt, is just one example of how the West combines beauty and business. It has an expansive portfolio of housing communities, business, hotels and retail and mixed-use properties.

“There are a lot of special places in the country that are urban, and there are a lot of mountain areas, but having urbanity in the mountains is really unique,” says Ben Teague, vice president of strategic development for Biltmore Farms. “It balances the sophistication of the cities and the serenity of nature. There’s a lot to be said for having nature and innovation together, and that’s what I think western North Carolina is.”

A MECCA FOR TOURISTS

Tourism is the region’s biggest cash crop. Buncombe County, home to Asheville and the Biltmore Estate, took in $2.6 billion in tourist spending in 2021, according to the latest data from Visit North Carolina, the state’s tourism development arm. Buncombe had the second-highest economic impact from tourists after Mecklenburg County.

When much of the travel and tourism industry struggled during the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic, tourism industry experts say Western North Carolina’s abundance of open spaces allowed for socially distanced recreation that continued to draw guests.

Now, restaurants and stores are again packed. Hundreds of small businesses that feed, clothe and entertain tourists beneath “Shop Local” banners give North Carolina’s mountain towns distinct personalities. From Asheville (population 98,000) to Maggie Valley (population 1,100), and Boone (population 19,000) to Bryson City (population 1,400), microbreweries, artists, retailers and recreation businesses attract visitors who

have been supporting the economy for multiple generations as well as newcomers.

Like any community that thrives on tourism, there’s a need to balance access for full-time residents. No downtown or mountaintop wants to fall into Yogi Berra’s old adage: “Nobody goes there anymore. It’s too crowded.”

“As a resident I have a tendency to go to outlying restaurants rather than right downtown during tourist season. I had a meeting downtown the other day and was able to get right in to eat without a problem,” says Kit Cramer, president and chief executive officer of the Asheville Area Chamber of Commerce. “We’ve partnered with Go Local Asheville (business alliance) on “Go Local” cards. They provide discounts to locals who buy them.”

Hickory

BUSINESS BEYOND TOURISM

While tourism is a major economic driver, North Carolina’s western counties are home to a variety of larger employers in sectors such as health care, manufacturing and construction.

Employers are lured by a strong existing workforce and a quality can also attract employees from outside the area.

Pratt & Whitney, a division of Raytheon Technologies, chose Buncombe County for its new $650-million aircraft component manufacturing plant. The recently opened facility makes jet engine fan blades and will employ about 800 people when it’s fully staffed. Salaries average $68,000 a year. Biltmore Farms sold 100 acres to Pratt & Whitney for $1.

“Given the number of high-paying jobs and capital investment, we believe this project will benefit the families of western North Carolina for generations to come,” says Biltmore Farms President and CEO John “Jack” Cecil.

The new positions aren’t just jobs, they are careers, Teague points out.

“There has to be that ability for someone to get on the career ladder,” he says. “And if the rungs are close enough, they can climb. But when you get on the career ladder and have to leave because you can’t get to the next rung, something’s broken.

“Pratt & Whitney is an ideal career-ladder employer. They will take you out of high school and pay for the skills training all the way up to where you have a six-figure [salary] job. When you can easily see the next rung and make it there, and have that pathway, that’s called economic hope. The average wage [for a machine operator] is $70,000-plus a year. Not only do you have a defined career ladder, but they pay you to move up. Those types of employers are important for our future.”

GE Aviation is another employer boosting the region’s visibility and workforce. In 2014 the company opened a $126 million facility to accommodate production of a revolutionary aircraft engine material known as ceramic matrix composite. CMC materials can outperform advanced metallic alloys, make jet engines lighter and more fuel efficient, and cut emissions dramatically. The Asheville plant is the first high-volume production facility of CMC materials in the world.

In 2018, the company announced plans to invest another $105 million in its Asheville operations, adding 131 new positions that pay 30% above the Buncombe County average wage and will increase the total workforce to 425.

Hickory, in Catawba County, is a leading hub for furniture making. This longtime North Carolina specialty carries on with state-of-the-art technology. Hickory Springs Manufacturing and Sherrill Furniture each employ more than 1,000 people while many other businesses in the furniture industry employ 100 to 500.

Lowe’s and Amazon have also invested in Western North Carolina. Each company has opened a distribution center of about 100,000 square feet in the past few years, adding to the area’s diversity of employers.

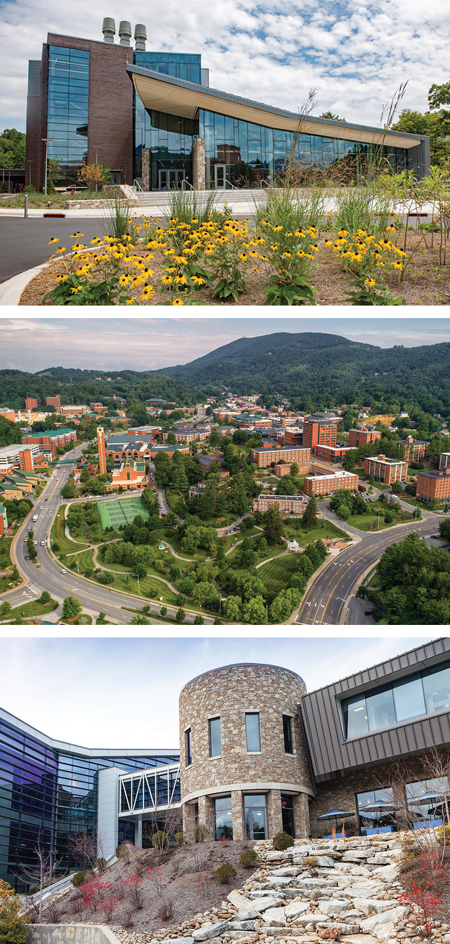

Western Carolina University, Appalachian State University, and

UNC Asheville are UNC System institutions.

Education in strong supply

Employers have a steady stream of college graduates and skilled potential employees graduating from more than 20 universities, colleges and technical schools throughout the western region. Through workforce development initiatives at Western Carolina University in Cullowhee, UNC Asheville, Appalachian State University in Boone and other higher-education institutions across the region, residents can prepare for well-paying employment that’s close to home.

“Our goal is to ensure that students see a meaningful path to working and living in the region, and they are connected to employer partners throughout their educational experience at Western Carolina University,” says Theresa Cruz Paul, director of WCU’s Center for Career and Professional Development.

WCU’s 2022 Career Fair PLUS+ hosted 150 employers, nonprofits and graduate school representatives. “The [Center for Career and Professional Development] works hard to ensure that each student can pursue their individual career goals in the state of North Carolina and in particular western North Carolina,” says Rich Price, WCU’s executive director of economic and regional partnerships.

Appalachian State University broke ground on its Innovation District in March. The Conservatory for Biodiversity Education and Research will develop economic opportunities across the region. “[It will] serve as a vital link between the campus and the regional community through education, research and outreach,” according to a university press release.

“One thing we learned during the pandemic is we don’t want to be over reliant on one particular sector, so I think diversification in growth and looking for opportunities to capitalize on new industries is something we’re looking at and our partners are looking at,” says Scottie Parks, impact officer for economic opportunity at Dogwood Health Trust, a private foundation improving the well-being of the region’s residents

and communities.

Dogwood’s Success Coach Partnership with Blue Ridge, Western Piedmont and Asheville-Buncombe Technical community colleges helps students stay on their chosen career tracks.

“[It’s] essentially case workers and counselors for community college students that will ensure that these students have what they need to complete their credentials,” Parks says. “We had a meeting with community college presidents early in 2021 to hear from them about what challenges they face and what we can do. And Success Coach rose to the top of the conversation, so we felt like we could get those three [colleges] funded, and we hope to engage with some of the others.”

Another example of the community supporting education and careers is the Asheville Area Chamber of Commerce program, Next AVL, named after the airport code for Asheville Regional Airport. The mentorship program matches students from the many colleges and universities with successful business owners or leaders.

“Some of these students may be the first in their family to go to college. We want to connect them to opportunities. The best way to find a job is through connections,” Cramer says. “It helps these young people establish relationships.”

It also encourages graduates to stay in the area where the mentorship and resulting connections can continue.

Other nonprofit organizations invest in the west and partner with schools to enhance education and quality of life.

Gateway Wellness Foundation helps local governments and nonprofits in Burke, McDowell, Polk and Rutherford counties address community needs.

Dogwood Health Trust, formed in 2019 when HCA Healthcare purchased Asheville-based Mission Health, distributes about $75 million in grants annually.

Gateway helps train people to construct modular homes from Kituwah Builders, which is owned by the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. Gateway and Dogwood also partner with McDowell Technical Community College’s Construction Trade Skills Academy to prepare students for general construction, construction project management and modular housing.

“[It] not only increases the affordable housing stock and the number of low-income, first-time homeowners, but it also increases the number of trained, certified carpenters and project managers to build the affordable homes,” says Neil Gurney of the Gateway Foundation. “This very technical aspect of the curriculum is coupled with additional courses on employability skills, communication and interpersonal skills. The student is being taught not only how to do the job but how to get the job and how to keep the job.”

With a lack of housing, only about 13% of the 12,000 people employed in Boone as of 2018 lived within the city limits.

MANAGING MOUNTAINOUS GROWTH

The increasing numbers of residents and businesses heightens ongoing demand for housing, road improvements, technology, health care and childcare. Numerous organizations and government entities are accessing and addressing these needs and coming at them in a variety of tactics from small fixes to large undertakings.

The city of Asheville is putting some of its streets on a diet as a way to combat congestion and help businesses. Charlotte Street has undergone a “road diet,” and other busy thoroughfares will also. The process reduces four lanes to three lanes and designates the center one a turn lane going either way.

“You’ve got that turn lane so it doesn’t block traffic behind you,” says Cramer. “It makes room for bike paths and allows broadening of sidewalks. It gives easier access to local retail along the way.”

The road diets are an example of a small initiative compared to the bigger considerations for infrastructure in a comprehensive plan for the next 20 years.

“We are balancing growth with the need for additional housing,” says Cramer. “Are there neighborhoods where they have higher unemployment rates? Can we find land adjacent to that to try to plant a business to be a job provider and simplify transportation issues?”

Government entities will provide incentives for businesses to invest in real estate in these areas.

“We are doing it in collaboration with surrounding counties,” says Cramer. “They have areas ripe for potential new development or redevelopment.”

Bowen National Research conducted a study on housing needs and supply throughout the western region in 2020. The six-month study examined population trends, income expectations, and supply and affordability for home ownership and rentals. It detailed the hourly wage needed to afford a two-bedroom rental unit in each county.

That amount ranged from $12.90 in Graham, McDowell, Mitchell, Rutherford, Swain and Yancey counties to $24.13 in Buncombe, Henderson and Madison counties. According to Asheville-based sustainable economy advocate Just Economics, the 2022 living wage — the minimum needed to meet basic needs — was $17.70 per hour in Buncombe County. It’s $13 in rural regions.

The housing study, funded by Dogwood Health Trust, clearly concluded there’s a housing shortage in western North Carolina, much like in the rest of the state and country.

The Bowen Research study on housing, is a first step to creating more homes.

“While some of the need is for market-rate homes, much of our housing shortage falls in the areas of transitional, supportive or affordable housing,” says Sarah Grymes, Dogwood’s vice president of impact. “Forming partnerships and leveraging other sources of revenue are going to be key to creating more safe and stable housing.”

With Dogwood’s backing, Gateway Wellness Foundation is building 31 affordable single-family homes in a Rutherfordton development that also will have 60 multifamily units and an Early Head Start location, which will support families and young children. Gateway also plans 26 affordable single-family homes in Marion.

Along with working to expand housing, child care, trans-portation and health care, Dogwood is improving broadband internet. It has partnered with the Institute for Emerging Issues at N.C. State University to fund the planning grants for all 18 counties and the Qualla Boundary so each will receive a $75,000 grant for broadband.

A recent Appalachian Regional Commission study found 22% of homes in western North Carolina lack broadband access, a deficiency highlighted by remote learning and work during the pandemic.

“We’re focused largely on filling needs that will remove barriers,” says Grymes. ■