Ramping up for a boom

Cummins Inc. Rocky Mount Engine Plant is a partner in a budding project called Regional Advanced Manufacturing Pipeline East, which pairs industry input with local community colleges and other organizations to train workers.

RAMP East matches workers and manufacturers to revitalize a big chunk of North Carolina.

Quick look: A new eastern N.C. workforce development program pairs manufacturers, local community colleges and other organizations to train workers.

By Edward Martin

Here, close enough is never enough. The 1.2 million-square-foot Cummins Inc. Rocky Mount Engine Plant is larger than a big-city shopping center. The manufacturing precision is incredible — the biggest of these engines will power 40-ton trailer-trucks the equivalent of four dozen trips around the globe before requiring overhaul.

The secret, says Paul Powell, the plant’s engineering manager, is no big thing.

Powell says Cummins holds “tolerances to the micron level,” which, for reference, is about 1/75th the size of a human hair. “It gives tremendous pride to our individuals to know that their process, their checks and their tool setups resulted in an engine that was perfect to the end-customer.”

On another day, John Judd, the plant manager who began in 1988 working on an assembly line, walks the plant floor and stops to fist-bump a technician in a blue smock.

Around him, racks of 35,000 different bar-coded, finely polished pistons, connecting rods and other parts, await some of the 170,000 engines — ranging from 65 to 600 horsepower — that the plant will build this year. The steady “braaaaap” of pneumatic wrenches wielded by goggled workers fills the air as giant, robotic arms tirelessly position heavy parts.

At one workstation, an inspector wearing surgical gloves runs his fingers over the satiny surface of an engine cylinder head, feeling for imperfections. At another, technician Dominique Battle flashes her employee identification under a card reader.

“Every employee [who] comes to their station to build an engine uses their badge to swipe in,” she says. “This says, ‘I built this engine, and I did it right the first time.’”

In advanced manufacturing, employees like Battle master not only technical skills but what workplace analysts call “soft skills” such as conflict resolution and problem-solving. “What makes us different is [that] we’re a team-based work system, and with that comes accountability and looking out for each other,” Judd says.

The Cummins Rocky Mount plant, one of the region’s largest companies with 1,800 employees, provides not only a close-up of Tar Heel advanced manufacturing, but it also shares a growing concern with its industrial neighbors in eastern North Carolina. Rocky Mount is 60 miles east of Raleigh.

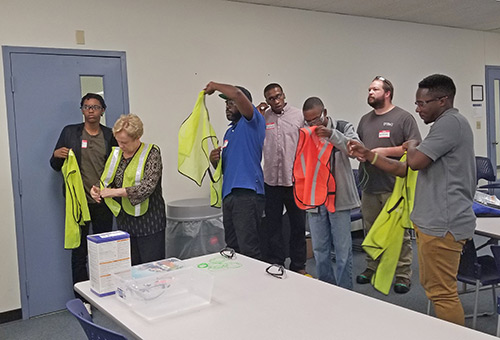

Edgecombe Community College’s Advanced Manufacturing Academy prepares students for careers in manufacturing, offering training in manufacturing concepts, math for manufacturing, OSHA 10 and forklift operation. Ron Sowers, Edgecombe Community College

Despite technology, these engines remain fundamentally human creations, and finding, training and hiring the workers who build them is a challenge in an area now experiencing a strong manufacturing boom.

Cummins is a partner in a budding project called Regional Advanced Manufacturing Pipeline East that’s shaping up to meet the demand. It’s a novel approach that pairs industry input with local community colleges, the Carolinas Gateway Partnership economic development organization, the N.C. Department of Commerce, the Economic Development Partnership of North Carolina and other agencies to fill that pipeline. It’s funded partly by a $641,000 award from the Golden LEAF Foundation, a nonprofit established in a lawsuit settlement intended to help replace lost tobacco-industry jobs.

The first step is regional thinking, says Peter Hans, president of the North Carolina Community College System and a former leader of Golden LEAF. “Workplace issues don’t recognize artificial boundaries,” he says. “RAMP East is a blended approach from every sector. We’re taking ourselves out of the old, traditional silos and figuring out how we can all work together. “

Innovatively, RAMP East takes advantage of what’s already in place rather than creating a new organization. That could take years when the impending boom doesn’t leave that luxury of time. Its principle is simple.

Community colleges, where customized training can be tailored to meet the needs of specific new or expanding industries, already have technical training such as machining, blueprinting or welding. Not to mention that industries such as drugmaker Pfizer Inc., another RAMP East partner and the region’s largest private employer with 3,000 employees, have vaunted, in-house training programs.

One of these programs can be found in a large, low-slung building full of classrooms adjacent to the Cummins plant, serving as the company’s training center. New employees cluster around desks as instructors discuss engine technology.

“We have 300 or 400 different roles here, but every one is a critical spoke in the wheel,” says Ralph Emerson, the center’s manufacturing director. “Every technician goes through a three-week employee orientation, and we have core skills, Cummins values, operations excellence, problem-solving, and value-stream mapping. We’re evolving into a manufacturing university that includes an engine tear-down section. It gives hands-on experience.”

Before employees are hired and reach that stage, however, RAMP East introduces them to advanced manufacturing. Deborah Lamm, a retired Edgecombe Community College president who promoted workforce development, is a RAMP East consultant.

“Edgecombe County and the region have a high unemployment rate historically, and I see this as an opportunity to turn that around and get people into the workplace who’ve not had the opportunity to get training, as well as to provide opportunities for growth and promotion for our existing workers,” she says. “RAMP East is a game-changer, but we’ve got to step up to the plate and provide the workforce.”

For years, agencies such as the Gateway Partnership have courted industries. Suddenly, their successes create a new problem — how to meet local recruiters’ promises to provide thousands of workers to run the plants. It’s a welcome dilemma here.

“We’ve taken our lumps, but we see a lot better days ahead,” says David Farris, a longtime car dealer and now president of the Rocky Mount Chamber of Commerce. For the 10-county region that RAMP East covers, he says those lumps began more than three decades ago when bedrock industries such as tobacco and textiles started withering as the result of global economic forces.

RAMP East pairs industry input with local community colleges, the Carolinas Gateway Partnership economic development organization, the N.C. Department of Commerce, the Economic Development Partnership of North Carolina and other agencies to help fill the workforce pipeline through hands-on industry training.

It didn’t seem so bad for a while. Rocky Mount maintained a core of homegrown financial institutions such as Centura Bank and others, including several local savings and loans. Other major businesses were headquartered in the city.

Then, in the 1990s, mergers began swallowing banks, the savings and loan industry collapsed nationwide, and iconic local companies such as Hardee’s Food Systems Inc., the fast-food chain once headquartered in Rocky Mount, were bought. In many instances, operations moved out of town. Devastating Tar River flooding during Hurricane Floyd in 1999 destroyed more local businesses.

Gradually, thousands of jobs evaporated. Today, Rocky Mount, the unofficial flagship of the region, has a population of about 54,000, down about 4,000 since 2000. But a hard-earned turnaround began in 2016.

CSX Transportation Inc., a Jacksonville, Fla.-based rail giant, unveiled plans for what is becoming a $160 million, 150-employee intermodal logistics hub called the Carolina Connector. The same year, Wilson’s Bridgestone Americas Inc. tire plant began a five-year, $200 million expansion, promising hundreds of new jobs and pushing its total payroll past 2,000.

In 2017, other manufacturers followed suit. Triangle Tire USA, a subsidiary of Chinese Triangle Tyre Co. Ltd., laid out plans for a $580 million, 800-job plant in the region’s Kingsboro megasite west of Tarboro, with production expected to begin in 2020. Next door, Corning Inc., the New York-based glass and fiber-optic giant, announced an $87 million, 150-employee distribution center.

The next year, Pfizer revealed a $200 million expansion at its local plant, boosting employment to 3,000 with the addition of about 800 jobs. The Aurora potash manufacturer of Saskatoon, Canada-based plant-nutrient giant Nutrien Ltd. and other partners now associated with RAMP East followed suit.

“We’ve got an enormous amount of work going on here, close to $1 billion in construction,” says Norris Tolson, president and CEO of the Gateway Partnership, one of the driving forces behind RAMP East. Recently, he adds, the partnership and other recruiters were pursuing nearly 50 other projects in Nash and Edgecombe, two of the 10 RAMP East counties.

Josh Tatum, the partnership’s director of research and special projects, including RAMP East, assesses the impact. “We see the need in the next 18 to 24 months to fill 3,500 to 4,000 advanced-manufacturing jobs in just the two counties, not even talking about the other eight,” he says. Community colleges in Beaufort, Edgecombe, Halifax, Hertford, Martin, Nash, Pitt and Wilson counties are taking part.

RAMP East tackles the challenges at the most basic level. The first is overcoming old ideas about manufacturing, which labor analysts say frequently are based on legacy industries such as textiles, often dangerous and known for poor working conditions.

“Today’s manufacturing world is much different from the manufacturing world of yesteryear,” Judd says. “People have been steered toward four-year college degrees, but now, jobs in manufacturing and trades are in high demand. We have to educate our community, parents and teachers, and I think we’re turning that tide.”

Only 27% of parents say they encourage their children to find jobs in manufacturing, according to a recent poll by the National Association of Manufacturers. It set a goal of raising that to 50% by 2025.

RAMP East’s corporate partners underscore another reason advanced-manufacturing jobs are increasingly attractive. At Wilson’s Bridgestone plant, average annual pay and benefits top $64,000, about $20,000 more than the county’s overall average. Triangle Tire has said it will offer $56,000 a year in pay and benefits. Corning’s distribution complex is expected to pay in the $45,000 to $48,000 range.

Landing those jobs, however, requires preparation and, in some cases, different attitudes. At a recent meeting at Edgecombe Community College, early RAMP East enrollees listened to instructors at one of the project’s Advanced Manufacturing Institutes programs initiated at the eight participating community colleges.

In the institutes here and elsewhere, students will get a 96-hour, semester-long introduction to the basic skills needed in workplaces such as Pfizer, Bridgestone and Triangle Tire. Through RAMP East, they may qualify for scholarship help, which could amount to $800 or more.

“We started the pilot class by targeting seniors from local high schools who graduated in June but didn’t have a plan for careers,” says Michael Starling, Edgecombe Community College’s business dean. The Advanced Manufacturing Academies assume students will learn specific technical skills either by taking those courses as part of their overall two-year associate degree programs or once they are hired through training by their new employers.

“We teach things like manufacturing concepts, an introduction to advanced manufacturing, working smart, critical thinking, working as a team and problem-solving,” Starling says, skills that will be needed regardless of which manufacturer hires them.

It was manufacturers that set the pace for the academy programs, adds Maureen Little, the N.C. Community College System’s vice president for economic development. “The industries reviewed the curriculum and agreed what content would be pertinent,” she says.

Now, here at Edgecombe and at Beaufort County Community College, the other pilot, academy students find themselves learning basic manufacturing math, Occupational Safety and Health Administration health and safety practices, and Lean Six Sigma Yellow Belt, the introductory level of a widely used industry program that relies on team efforts to reduce waste and improve manufacturing consistency.

Little says the industries “will participate in job and career fairs and allow employees to tour plants,” possibly ending in job interviews.

Much is riding on RAMP East. Tolson estimates as many as 25,000 workers in its 10-county area indicate they’re looking for new or better jobs. RAMP East, he adds, could have as many as a thousand participants in its pipeline by 2020.

RAMP East recognizes that not all of those are newly created jobs. Lamm says RAMP East intends to accommodate “incumbent” or already employed workers. Regardless of what the RAMP East partners make — from tires to plant nutrients to injection-molded plastics — they face a shared challenge.

At Cummins, Emerson says the company will have to replace as many as 400 workers eligible for retirement over the next six years, not including normal turnover or those needed for possible expansions. Plus, adds Cummins spokeswoman Katie Zarich, the company constantly upgrades its technology but relies heavily on retraining to fill those roles.

“This is not just a Cummins challenge,” Emerson says. “This is a challenge facing the United States, with the baby boomers retiring.”

The principles of RAMP East could also spread across the state, Little says, tailored to the kinds of industries growing there. “RAMP East is certainly a model that can be replicated. Not just for manufacturing, but say health care, information technology or whatever is driving the local economy.”

The Northeast “needs a shot in the arm as much as anybody in our state,” Hans says. “And without the talent pipeline we’re creating, we can’t do that.”

PULLING RANK

Military skills and training generate new jobs.

In a small mall in Wilmington, mothers with fretting children and retirees with unexplained aches jockey in Masonboro Family Medicine’s parking lot. It’s a long-established practice, founded by two of its four physician assistants in 2003.

In a small mall in Wilmington, mothers with fretting children and retirees with unexplained aches jockey in Masonboro Family Medicine’s parking lot. It’s a long-established practice, founded by two of its four physician assistants in 2003.

Andrew Illobre sees a range of patients from pediatric cases to adults with diabetes and high blood pressure. In a region known for sunny beaches and outdoor activities, he has a special interest in skin cancer and sports injuries. Fellow physician assistant Kim Martin shares more than his medical interests — Illobre is a Coast Guard retiree and Martin is a former Army reservist.

Up the coast in Hampstead, the ink is barely dry on Lee Colter’s discharge, but the Marine veteran is enthusing about business prospects for him and wife Renea in the Port City. Grumpy Grandpa’s Coffee is a mobile coffee shop, making the rounds at farmers markets and local events. Renea’s grandfather, a Navy veteran, inspired the name, and Lee’s robust facial hair inspired their other fledgling enterprise: Belligerent Beard, which makes and sells a line of beard oils and washes they make online and at about a dozen retail outlets.

“More than anything, being military has opened doors for us,” Colter says. “You learn leadership, and it’s a great asset when you’re forming a business.”

The clinic and Colter’s startup represent an often unnoticed success story for North Carolina: Their owners are among 84,000 military veterans who’ve established businesses here, becoming part of the larger military and defense economic sector that pumps $66 billion a year into the state’s economy.

“We combine both active-duty military and veterans in how we look at the military’s impact,” says Marine veteran Larry Hall, secretary of the N.C. Department of Military & Veterans Affairs. He heads the state’s N.C. Military Affairs Commission, established in 2013 by the General Assembly to protect and build the state’s military resources. “We recently had about 730,000 veterans and 100,000 retirees living in North Carolina, and our state is No. 2 in veterans living in rural areas.”

About one in 10 businesses in the state is veteran-owned.

Massive military bases such as Fort Bragg, with a population of more than 60,000 military members and civilians, and Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune, with close to 40,000 Marines and civilians, capture most of the attention. But Hall says veteran-owned businesses show that North Carolina is succeeding in attracting and keeping former military members such as Illobre, Martin and Colter.

Hall and N.C. Secretary of Commerce Tony Copeland portray the armed forces as a massive repository of skills and talent waiting to be tapped through military-friendly programs, whether by veterans setting up their own businesses or becoming executives or employees of civilian industries and enterprises. Copeland cites two of the state’s high-profile advanced manufacturers: Honda Aircraft Co. in Greensboro and Spirit AeroSystems in Kinston. Now employing about 1,600, Honda has invested about $250 million. Similarly, Spirit employs about 800.

Many of their potential workers are former military members trained while on active duty. “We need to figure out how to access that and bring them back into the private sector,” Copeland says.

Hall and others say the military is concentrated in eastern North Carolina. Fort Bragg, Camp Lejeune, Marine Corps Air Station Cherry Point, Marine Corps Air Station New River, Seymour Johnson Air Force Base, Military Ocean Terminal Sunny Point and the U.S. Coast Guard Base at Elizabeth City are all on or east of the Interstate 95 corridor.

“We’ve got, combined, 100,000 active- duty and 21,000 reserve and National Guard personnel, plus 22,000 or so civilian employees,” Hall says. “That means we’re talking about a total of about 140,000 or more working, active-duty personnel. We’re responsible for about $66 billion a year coming into the state through the military and veteran communities combined. One way to look at it is, we’re the second-largest industry sector in the state, and we’re a value-added segment of the economy because most of the money is federal. We call ourselves a hidden economic engine.”

One of the state’s smaller major bases, Seymour Johnson Air Force Base nevertheless has an annual economic clout of more than $700 million, with its 12,000 active-duty personnel, civilian employees and dependents.

At Fort Bragg, the North Carolina Military Business Center estimates the Army pumps $31 million a day into the region. In one way or another, more than 250,000 people in the region have ties to the base. Hall says the value of the military training is inestimable.

For one thing, he says, former service members like Lee Colter “are tested, trained and evaluated in leadership.” When they make the transition to civilian life, they retain those characteristics and skills. “We call them culture carriers. When you hire military, they bring those elements to the workplace.” The military typically spends tens of thousands of dollars training people in fields such as aviation maintenance and computer technology that are in demand at Honda and elsewhere.

The N.C. Department of Commerce and the state are pumping millions into programs such as North Carolina for Military Employment, which conducts dozens of hiring fairs annually, and the N.C. Military Business Center, based at Fayetteville Technical Community College. The latter group puts Tar Heel businesses on the trail of Defense Department contract opportunities.

Cary-based North Carolina Veteran’s Business Association helps former service members start businesses and lobbies politicians to support veteran-friendly legislation and regulations.

“We’ve got about 22,000 people a year transitioning from active-duty on bases in North Carolina, and we’re trying to keep them in North Carolina,” Hall says. “In eastern North Carolina, the primary economic drivers are the defense industry and our universities,” he says. “The folks there know how important the military is to their economy.”